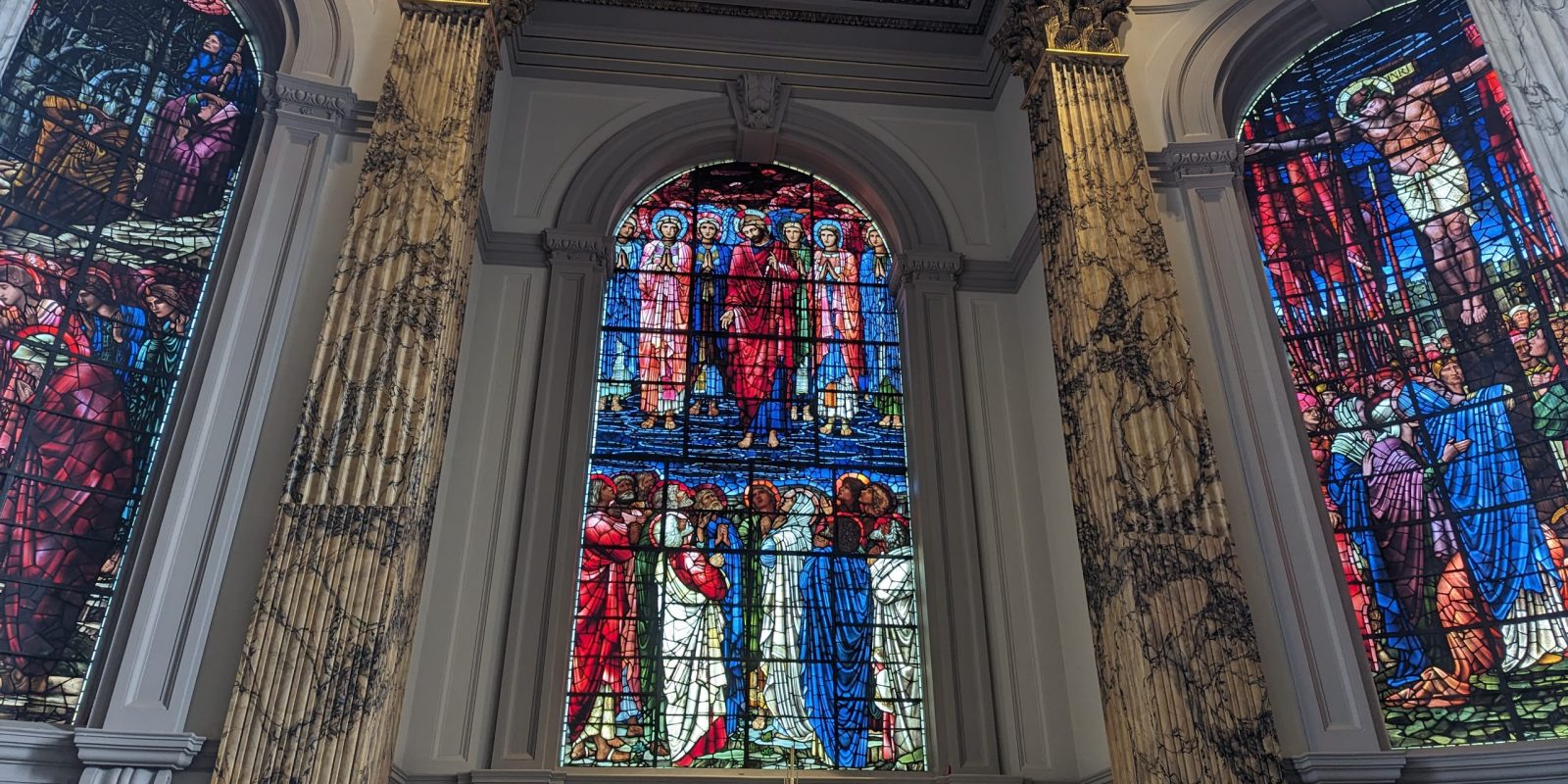

Birmingham Cathedral is home to four stunning stained-glass windows – considered among the finest in the world. The windows were created by the famous Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones and his lifelong friend William Morris. They depict four significant events from the life of Christ, and continue to inspire and guide worshippers to this day.

The first window to be installed was The Ascension, in 1885, and was originally meant to be the only stained-glass window in the building. This was followed by The Nativity and The Crucifixion windows on either side two years later in 1887. The Last Judgement was the final window to be created for the west end of the church, under the tower, in 1897.

The windows are set into rectangular metal frames, allowing the sun to shine through the windows, casting vibrant colours across the floor and the walls of the cathedral throughout the day.

The windows were cleaned, repaired and conserved in 2023 as part of the Divine Beauty Project – ensuring they remain as one of the city’s greatest treasures, to be enjoyed by future generations.

Below you can find out more about the window’s history, their creators, the scenes they depict, and the work undertaken to ensure they are maintained for many more years to come.

“The windows provide me with a feeling of awe, belonging, and provide four reminders of my faith. The cathedral’s side windows allow the Burne-Jones and William Morris stained glass to project into the whole building, thereby carrying four straightforward Christian stories to everyone. “

Joe – Volunteer

The Windows

About our windows

Initially, the commission was for a single stained-glass window, representing the Ascension, for the central opening. It was in place in 1885. It was only two years later that Burne-Jones saw, for the first time, the Ascension window in situ. He was so overcome with the emotional impact of the finished window as he stood in front of it that he at once suggested designing two further windows to fill the spaces on either side. After discussion between artist, architect, funder, Rector and manufacturer, it was agreed that the two further windows should represent the ‘Nativity of Christ’ and the ‘Crucifixion of Christ’. Burne Jones aspired to create artworks that enhance ordinary people’s ability to connect with Christ. He had stated that he wanted to create large works for vast spaces, his constant adage being ‘by the people for the people’.

A fourth commission was provided in 1898 to fill the west window with ‘The Last Judgement’ as a memorial to Rector, Henry Bowlby who had died in 1894. It is considered to be Burne-Jones’ masterpiece, though sadly he never saw the finished window as he died in the year it was installed.

Burne-Jones’s slender, beautiful elongated figures echo medieval images observed on the facades of the French cathedrals such as Chartres, which he had visited as a young man. Many of the colours are symbolic and are influenced by Byzantine iconography. Christ’s robes are red when he is depicted moving from Earth to Heaven (as in the Ascension window) and white when he is depicted in Heaven or coming down to Earth. The Virgin Mary is traditionally shown in blue robes.

The strong views of the benefactor Emma Villers Wilkes, who provided the finance for the project, were influential in the design of the two side windows. She was a devout High Church Anglican who regularly attended services at St. Philip’s, and the donated funds were in memory of her brother. She insisted that the traditional representation of oxen in Nativity scenes was un-Biblical, and that the Crucifixion should not be blooded and gory, as was often the case in medieval scenes.

Morris had been experimenting with colour, in close collaboration with Burne-Jones, using the technological advances of the age, special colours and a larger colour palette; for instance the rich pink of some of the robes is unusual.

These colours have not faded over the years. The detailed features of the windows were painted on with ground glass, stabilised with oil and water and re-fired, bonding them into the structure of the glass, which has prevented fading over the passage of time. During the recent restoration project, the conservators noted the good condition of the detailing and colour of the panes, indicating a high level of craftsmanship in the creation of the windows.

The restorers found that the glass in these windows is considerably thicker than usual, at around seven to ten millimetres, compared to the more usual 3 millimetres. The lead work was also used to create parts of the image, such as the definition of the folds of the cloaks.

Particularly interesting, and delightful, are the William Morris textile designs that pop up unexpectedly: Jesus's loincloth in The Crucifixion window is more or less exactly Morris's famous Willow Boughs design. Mary in The Nativity window wears a beautiful robe of sinuously entwined flowers and leaves peeping from under her blue mantle. St Peter in The Ascension has acanthus leaves on his robe and lovely daisies on his cloak.

Common to all the windows is the contrast and connection between Heaven and Earth. The same themes spread through the images, slender, androgynous angels with long graceful fingers, their expressionless faces contrasting with the vibrancy of the mass of humanity that gathers on earth.

Some of the details of the superb craftsmanship are only apparent in close-up: for example, the feet of the Apostles, complete with individual toenails in The Ascension window, or the wonderful leggings and chain-mail bindings of the centurion on the far right of The Crucifixion window.

Our windows were designed by famous and locally-born Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, and his friend William Morris.

Burne-Jones was born in 1833 into a middle-class family at the heart of Birmingham’s industrial success. They lived in a house in Bennetts Hill just across from St Philip’s, and was baptized here as a baby. His mother, who was a jeweller, died within six days of his birth. He was a pupil at King Edward’s School before attending the University of Oxford. As part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, he reacted against many de-humanising aspects of the industrial world of the Victorians, looking instead for inspiration from medieval art, religion, myths and legends. Burne-Jones was one of the later members of the movement and his superlative talents ranged across paintings, stained glass windows and tapestries.

William Morris was born in Walthamstow, east London in 1834, into a wealthier family than that of Burne-Jones. The inheritance of his middle class surroundings gave him the freedom to use his talents in the pursuit of his own desires. He became a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, championing a principle of handmade production that didn’t chime with the Victorian era’s focus on industrial ‘progress’.

Morris and Burne-Jones met at Oxford University and they became lifelong friends. Burne-Jones introduced him to a group of students who became known as 'The Birmingham Set' and 'The Brotherhood', and who enjoyed romantic stories of medieval chivalry and self-sacrifice. They also read books by contemporary reformers such as John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Carlyle.

Morris and Burne-Jones had begun training for the priesthood, but after an architectural tour of northern France, they realised that their gifts and energies would be better spent in the expressiveness of art than in ordained priesthood.

Burne-Jones's connection with Dante Gabriel Rossetti – a central figure in the Pre-Raphaelite group – soon led to Morris working with Rossetti as part of a team painting murals at the Oxford Union.

Subsequently, in 1861, Morris, along with Burne-Jones and other leading members of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, set up their own decorative arts firm, which later became Morris & Co. The prospectus announced that the firm would undertake carving, stained glass, metal-work, paper-hangings, printed fabrics known as chintzes, and carpets. The decoration of churches was from the first an important part of the business.

A number of prestigious commissions followed, including at St. James’s Palace and at what later became the Victoria and Albert Museum. At the same time Morris & Co. were responsible for work in a series of churches all over the country. Morris died in 1896 and Burne-Jones in 1898.

The Ascension window

The Ascension window depicts Jesus parting with his followers and ascending into heaven forty days after Easter. It was installed in 1885 and intended to be the only stained-glass window in the building. Inspired by its beauty, Burne-Jones decided to design two more shortly afterwards. Its size, scale, central position, and dazzling colours draw the attention of anyone visiting the cathedral.

Christ is at the scene's centre-top, with brown hair and a short beard. His head is framed by a cream halo with three sections decorated with St George’s Cross, symbolising the resurrection victory.

He wears deep red robes over a navy blue, ankle-length tunic. Red symbolises divinity, and blue represents his humanity. Six Angels wearing brightly coloured robes are gathered around him; their pale, smooth-skinned faces, under light brown hair framed by halos, stare out impassively, hands clasped in prayer. While most of the Angels’ wings are striking, vivid red is in all four windows. However, two of these Angels have blue wings, one navy and the other a soft powder blue.

Christ looks down at his disciples gathered in their fear and wonder and beyond them to humankind. His left hand is raised, one finger extended, in the traditional iconic symbol of blessing. His open right hand reaches down to the people, symbolising his invitation to draw near.

Like all the windows, the design is divided into two halves across the centre. Christ and the angels stand on a smooth, dark blue surface patterned with lighter blue circles, giving a watery effect. This surface forms the distinction between Heaven and Earth. Burne-Jones said he wanted to show ‘heaven beginning six inches above our head, as it really does’. Apart from a narrow line of distant blue sky and brown hills, the heads of the people on earth seem almost to brush the foot of Heaven.

The eleven remaining disciples also crowd below Christ, who ascends to heaven forty days after his resurrection. There is a woman in the centre of the crowd below. She wears a white robe but has glimpses of blue in her arms. The woman is believed to be either Mary, the mother of Jesus, who is often depicted in blue robes, or Mary Magdelene. Her eyes are fixed on Jesus, with her hands clasped at her breast. Her white robe covers her head and drapes down over her pale blue gown. More research is being undertaken to confirm which Mary this figure represents, as no women are described as present at The Ascension in scripture. Still, one or the other of the famous Marys is often depicted as present in artistic interpretations.

The disciples’ robes are a variety of colours. Unlike the pale angels, their skin tones range from Mary’s pale, delicate face from pink to brown, a more accurate representation of the diversity of the population from which the disciples emerged. Their bare feet are in sandals; they are standing on flat grey stones, with little tufts of greenery poking through the gaps.

Some of the most intricate details of this window can be found in the feet and sandals of the figures, where double and triple plating is used to create different colours and depth.

The Nativity window

The Nativity window tells the story of the birth of Jesus, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke in the Bible. The window is positioned opposite the crucifixion window - highlighting the contrast and anguish of the two events.

Wealthy Birmingham resident and congregation member Emma Chadwick Villers-Wilkes paid for both these windows in memory of her late brother. She specifically requested that there should be no oxen in the Nativity scene, as she considered them to be ‘too brutish

The top of the left-hand side is filled with a crowd of scarlet-robed angels gazing down from Heaven, curving up and around within the edge of the arched top of the window. Their pale faces and golden hair are framed by halos as they look down on the rustic scene below. Some of their slender hands appear, fingers raised in praise.

Below the curving crowd of angels is a forest of trees with light brown tree trunks and a twisting mass of dense branches. To the right, three shepherds look upwards up at the angles, shielding their eyes – their flock of sheep to the centre-left of them below.

They stand on pale, smooth rocks, each one a little higher than the other. The topmost shepherd wears a dark blue robe, leaning on a sturdy staff, then one in a red robe and the third in orange, shielding their eyes. The shepherds were outsiders in their society. Burne-Jones has placed them at the top, showing that in the Coming of Jesus, the world is turned upside down.

This image has a wonderful sinuous quality because the dividing line is not horizontal but formed by the slope of the cave. Below, shallow arching lines of brown, narrow pieces of stone form the roof of a dark cave where the baby has been born to the holy family. The cave is an unexpected change from the more familiar stable; the lead work of the window emphasises the gloomy depths that stretch back into the cave’s interior. The pale brown and yellow curving stones of the cave/stable roof divide the upper register from the lower. The cave (which recedes into a dark interior) is a likely representation of the birthplace since the Holy Land is known to be home to many caves which have long been used to house animals in the winter months or even as dwellings.

Mary kneels on a flat ledge of small rocks. She leans tenderly over the baby, her shape mirroring the curve of the angels and the cave roof. Her head is veiled in white, framed by a scarlet halo patterned with roses, and she is clothed in a dark blue robe. She holds her clasped hands just under her chin. The hem of her blue robe spreads across the rock under the little bundle of white cloths that form a makeshift bed for the baby.

An interesting (and probably accidental) feature of the design is that when the sun is low in the sky, the first morning light shines through through the winter months and illuminates the baby.

Jesus is tightly wrapped in white swaddling bands, his pink arms emerging, and his tiny rounded face, framed with golden curls and a halo, lies on a makeshift pillow. Joseph, depicted as an older man, stands on the right in a red robe. He bends over the child, his hands raised. Behind Joseph, three angels gather close, their haloed heads bent to gaze down at the baby. There are jewels on their foreheads.

The Crucifixion window

The Crucifixion window depicts the death of Jesus, and it is opposite the Nativity window in the cathedral. This highlights the contrast and anguish of the two events.

In the centre of the scene, Christ hangs on a large cross, surrounded by tall red banners across the background. He wears a white loincloth decorated with delicate William Morris-designed floral patterns. His head is turned sideways, and a narrow green crown of twisting thorns encircles his brown, shoulder-length hair.

A glowing white halo frames his head, and faint pale blue lines and the three arms of a cross symbol used in Byzantine Icons of Christ are in that halo.

Christ's bare torso is robustly muscled; the pieces of glass depicting his chest appear to be wrongly arranged with mismatching anatomical shapes and shades of colour. This disarray and dissonance suggests the artist is powerfully representing the man's anguish as his beaten, nailed body carries the burden of the sins of the world.

His arms are stretched along the crossbeam; small marks show on the palms of his hands where the nails have been driven in. A parchment with the letters INRI has been pinned to the top of the sturdy dark wood cross. Iesus Nazarenus, Rex lauaeorum, translates as Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.

In the distance, a broad sky merges different shades of blue above the crenellated towers of the walls of Jerusalem. Little yellow windows glow in the brown walls, the emanating lights indicating that people in Jerusalem were carrying on with their daily lives whilst the crucifixion takes place outside the city walls.

Wealthy Birmingham resident and cathedral congregation member Emma Chadwick Villers-Wilkes paid for both these windows in memory of her late brother. She requested that there should be no blood in the scene of Christ's death. However, Burne-Jones' use of a blood-red banner flanking the crossbeam suggests to the viewer the blood pouring out of Christ.

At the foot of the cross, a mass of faces look up at the figure of Christ - their darker skin tones representing the Middle Eastern population. In the foreground on the left, three grieving women cluster close on the rocky ground around the base of the cross. Two have their heads veiled in white; one wears a navy robe, the second a rose-coloured robe, and the other is crimson; they reach tender hands to Mary, Jesus's mother.

She stands closest to the cross, just below Christ's nailed feet. Her distinctive blue robe covers her head and drapes above her white dress. Her clasped hands lift her face to gaze up at her son.

Mary Magdalene, one of Christ's most devoted followers, who was erroneously identified in the Middle Ages as a penitent prostitute, originating a long-accepted tradition, has fallen to her knees at the foot of the cross, her face buried in her hands as she weeps. She is dressed in red; the colour and the curve of her bowed back give her an immediacy in contrast to the stillness of those around her. A golden halo frames her head.

Jesus's beloved disciple John stands with Mary on the right, at the foot of the cross. His scarlet cloak drapes in folds around his green robe. His brown hair falls to his shoulders under a green halo that matches his robe. His smooth, youthful face is lifted to Jesus, his hands clasped at his chest.

On the far right, a helmeted soldier in a red cloak aims a tall spear towards Jesus's side, referring to St. John's Gospel. Like the window on the opposite side, shallow ledges of the rocky ground fill the bottom of the scene.

The Last Judgement window

The Last Judgement is widely recognised as the finest example of Burne-Jones' work, depicting the return of Christ and his judgement on humanity. The window was a memorial to Bishop Bowlby of Coventry, who was Rector of St Philip's from 1875 to 1894.

Christ sits at the very top of the window, robed all in white, seated atop a double rainbow, a symbol of hope and the covenant between God and humanity. A green crown of thorns encircles Christ's long reddish-brown hair, which falls beyond his shoulders. His head is framed by a brilliant red halo.

Christ's bearded face is calm as he offers a benevolent open palm. Both of his hands clearly show the stigmata, the wounds left by the crucifixion nails. An elegant curving line connects through the long folds of Christ's robe to the swooping figure of the Archangel below and the slender curving trumpet at his lips.

Christ and Archangel Michael are flanked by an arced mass of sixteen red-robed Angels, each holding up a meticulously detailed object. They include the leather-bound Book of the Judgement, one of three mentioned in Revelation, and the key to the gates of Heaven on a long double golden chain, which refers to the binding of the dragon in Revelation 20. Seven others hold vials, referencing the seven bowls of God's wrath, as described in Revelation 16.

This window is best viewed in the afternoon when the sunlight shines through, casting vibrant and colourful reflections of the stained glass across the cathedral floor.

As with the other windows, the angels in 'The Last Judgement' are based on a sketch of the head of Margaret, Burne-Jones' beloved daughter. Burne-Jones would have seen plenty of 'Last Judgement' windows in France and frescoes in Italy. Usually, these images aim to terrify the viewer into goodness. Instead, Burne-Jones offers a compassionate Christ with his Heavenly Host. However, those waiting to be judged still appear very afraid.

There are meticuous details, such as the elaborate gold crown worn by the figure clothed in red on the right of the window. The angels hold a range of beautifully intricate objects, such as the leather-bound Book of Judgement and the key to the gates of heaven.

This dramatic scene has a central, cubist-style dark brown band separating heaven from earth. This features a ruined cityscape, at once universal, with Renaissance towers. At the same time, we see industrial Birmingham and what we understand to be the Town Hall.

On Earth, at the bottom of the composition, a mass of fearful people huddle anxiously together. A young family stand centrally. The husband enfolds his wife in his arms. She shields her eyes with one hand as she gazes up to the heavens whilst clutching her baby tightly in the crook of her other arm. A small child dressed in white clings tightly to his father's burgundy robes.

A barefoot man with his back to us wears an elaborate gold crown to indicate that Jesus has returned to judge the rich and the poor. Another two apprehensive women on the left of the scene clasp one another tightly, standing on top of a stone tomb. Beneath their feet, figures of the dead appear to be crawling out of their graves.

The Divine Beauty Project

Initial funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund enabled a detailed investigation of the condition of the windows to take place in 2015. Unfortunately, this work uncovered significant damaged in a number of places, including portions of glazing that were missing or cracked. The conservation of the windows took place in 2023, as part of the Divine Beauty project. This work was enabled with thanks to a grant of £641,200 in National Lottery Heritage funding.

The work removed a substantial build up of debris and to repair areas of cracking, failed leading and paint loss. Visitors were able to see this work as it happened from an accessible platform and take part in a range of engagement activities.